The neurosciences of trust

What can neuroscience teach us about trust in human relationships ? The human brain, that astonishingly powerful organ, is still mysterious in many ways. Neuroscience helps us to see more clearly how we relate to trust. Among other things, within organizations, the quality of human relations depends largely on the level of trust. A 2020 study by Great Place To Work showed that companies with a strong culture of trust perform twice as well, have 50% lower staff turnover, more committed employees and greater customer satisfaction. Here we explain the importance of trust according to neuroscience.

Trust according to neuroscience: instinctive or rational?

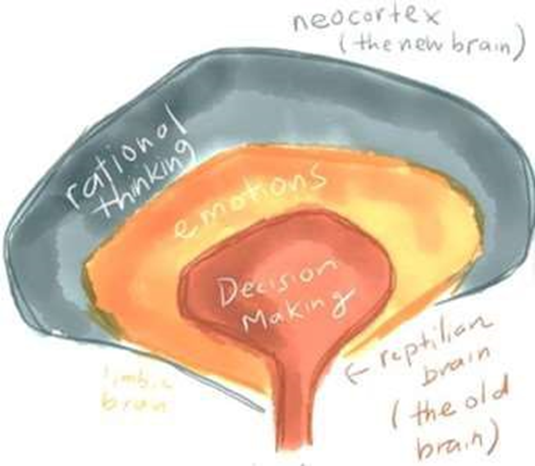

According to neurobiologist Paul D. MacLean’s 1960 theory, our brain is schematically represented by 3 subparts:

- the reptilian brain, the most archaic in human evolution, the first to develop in the foetus, and above all the one inherent in our primary instincts (feeding, protecting and reproducing);

- the limbic brain, the seat of our nervous system, in charge of our emotions, judgments and learning;

- the neocortex, our rational brain in charge of our conscious decisions, as well as our ability to analyze, visualize and create.

Even if each part has its own purpose and distinct functions, the fact remains that our 3 brains are remarkably collaborative.

Trust by instinct

As social beings, we have long understood the power of the group. Coming together ensures our survival in the face of danger (reptilian brain). Trust is a feeling induced by the limbic brain in the context of human relationships. It triggers the production of oxytocin, a neurotransmitter known as the bonding hormone. The hormone is then distributed throughout our body by our nervous system. From the very first hours of our lives, the natural trust intrinsic to the emotional bond between mother and child triggers the production of breast milk. This process, carried out by our 2 oldest brains, nevertheless limits our capacity to bond.

Streamlined trust

Our instinct favors the protection of our close circle of friends and family. The good news is that the neocortex also plays a role, analyzing our environment through our senses, according to its own perception. It can then try to widen the circle, aware that the more allies we have, the more certain oour survival.

In the professional context, enlarging the circle of people we trust translates into the opportunity to optimize our ability to achieve our objectives, and therefore our performance. Conversely, the fear of being rejected by the group is provoked by the primal survival instinct inscribed in our ancestral memory. We have everything to gain from cooperation. Establishing a relationship of trust is therefore an effort that relies on our capacity for empathy. The principle of mirror neurons enables us to sense the emotions of others, and to deploy a congruence between our verbal and our para-verbal.

However, the process of bringing the brain into awareness is energy-intensive. When the neocortex (and in particular the prefrontal) has consolidated the instincts of the reptilian brain, through a period of awareness in its relationship with the other, its satisfaction leads it to be able to reduce its attention. He can then concentrate his efforts and energy on other missions. So it’s teamwork for all 3 parts of our brain: trust, essential to our survival, can be instinctive, but also conscious and therefore developed.

Trust: the keys to a virtuous or vicious circle?

A human being only exists through the environment in which he or she evolves. The systemic vision helps us to understand how we interact with our environment. Our perception of it triggers a representation by our brain, which in turn induces emotional and physiological reactions, which in turn induce our thoughts, language and behavior.

These then impact our environment and our relationships with others. This vicious or virtuous circle applies equally to confidence. Self-confidence helps develop the trust given to others, which in turn feeds the trust received from others, which in turn feeds self-confidence… and so on.

Healthy trust

Cognitive biases, which act as filters between reality and our interpretation of it, can lead us to make the wrong choices. When it comes to trust, making the wrong choice can be synonymous with disappointment, or even sense of betrayal. Naïve or consolidated trust is then broken, often irretrievably. Developing the ability to trust is an art to be handled with tact, so as to remain in a zone of healthy trust: neither too much nor too little. Avoiding distrust or, on the contrary, arrogance, is a skill we can develop by becoming aware of our own states and ways of perceiving others.

Trrust in a coaching process

Thanks in particular to coaching tools such as knowledge and self-esteem as well as interpersonal relationships, we can act on our individual accountability and collective confidence. Although the brain far prefers what it already knows and is wary of what it does not know, its plasticity opens the doors of possibility to create new neuronal grooves (synapses) and learn to build relationships of trust with those around us and whom we need to access performance.

“Organizations are no longer built on strength, but on trust.” Peter Drucker in The Effective Manager.

👉 if you’re curious about measuring the level of trust within your organization or for yourself with Startrust, contact one of our certified Startrust Advisors.

👉 if you’re curious to find out more about the importance of trust in the managerial posture , discover the conference by Éric Chabot, co-founder of Startrust.

Sources :

https://www.cairn.info/revue-des-sciences-de-gestion-2009-5-page-61.htm

Une affaire de neurobiologie, Nadia Medjad, Inflexions 2022/3 (N° 51), pages 167 to 175 https://business.lesechos.fr/entrepreneurs/efficacite-personnelle/0601518360079-pitch-seduire-les-trois-cerveaux-331070.php